5 Ways Writers Can Prep for 2025 Goal Setting

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

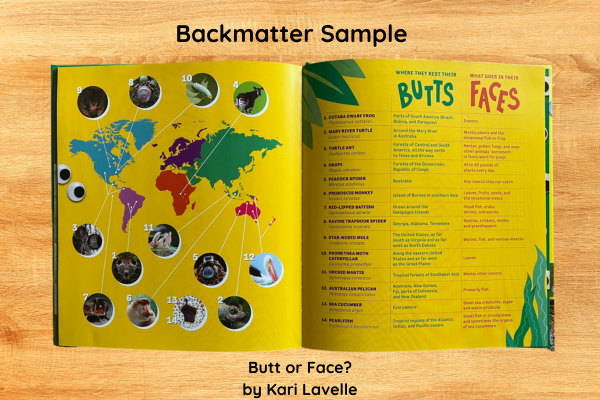

Nonfiction picture books, educational books, and even some novels and fiction picture books include information beyond the main bulk of the book. When this information is positioned after the main text, it is referred to as backmatter.

For example, my picture book biography Grace Hopper for Rourke’s “Women in Science and Technology” series, includes a timeline of major events in her life, some of which were not mentioned in the main text, as well as a glossary, an index, and classroom support materials (text-dependent questions and an extension activity). It’s not uncommon for education publishers to include backmatter, but trade publishers are discovering how much backmatter brings to a book, which is making backmatter more and more popular.

Now, not every nonfiction book includes all of these, but publishers like to see rich, well-crafted backmatter as it helps with sales and how useful children’s books can be in the classroom. Having said that, not all nonfiction picture books include backmatter, nor do all historical fiction novels. But it’s worthwhile to understand what purpose backmatter serves so you can decide if you need some for your work-in-progress.

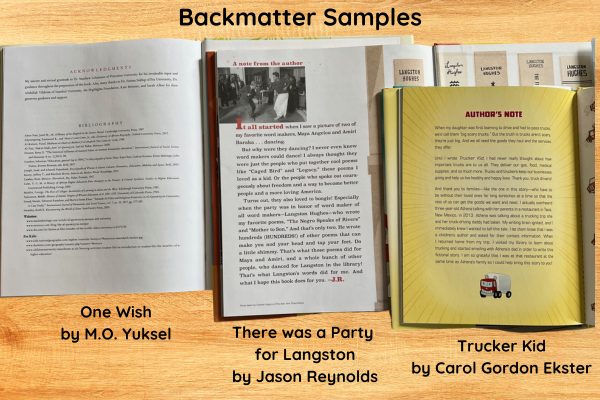

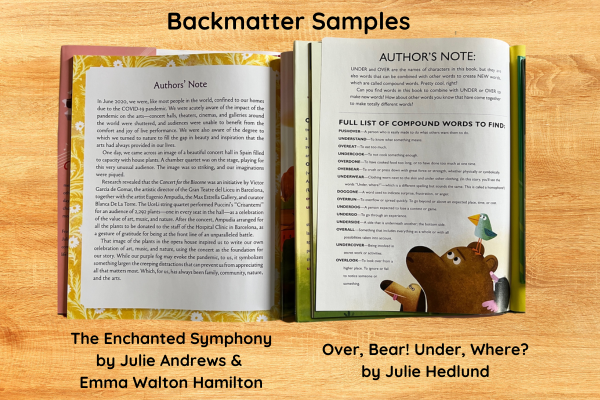

Because picture books are so short and novels are so focused on story, sometimes it can be helpful for the reader if the author adds backmatter to give context to specific elements, events, and even characters of the book. This often comes in the form of author notes or illustrator notes. These may be used to better explain the historical setting or real-life events in the book, or they can explain or expand upon the science necessary to properly understand the story.

The context added by backmatter doesn’t only mean objective context. Author’s notes and illustrator’s notes are a great place to add personal context as well. As Carol Hinz of Millbrook Press and Carolrhoda Books said, “An author’s note or illustrator’s note can be a great place to include a creator’s personal connection to a book’s subject matter.” This not only helps readers understand the book better, but also gives them a sense of the process of creation. In a way, it’s a peek at answers to the question, “Where do you get your ideas?”

An example of this kind of subjective note can be found at the end of Jason Reynolds’ There Was a Party for Langston. The author’s note explains how the picture book was inspired by a photo of Maya Angelou and Amiri Baraka dancing. It made Reynolds look at some of his most admired writers in a whole new way. And that led to a book that celebrated poetry, and especially the poetry of Langston Hughes, as something to tap your toe to.

Even in novels, the backmatter can be quite extensive. In Alan Gratz’s novel, Refugee, the backmatter includes a map and 11 pages of information on the real-life situations and people that the novel is meant to illuminate. The backmatter even has a section subtitled, “What You Can Do,” to help readers who are spurred to action by the story. Backmatter is especially important in novels about challenging experiences because they can be introductions to times and events the reader may never have known existed before picking up the book.

Not surprisingly, the author’s note reveals how difficult it is to truly know what happened with people in hiding for their lives. The backmatter for this novel is a fascinating read all by itself.

It’s not uncommon for the backmatter in a nonfiction picture book to be longer than the text of the book itself. As a result, backmatter (such as author’s notes or more in-depth looks at the topic) is never considered part of your word count. A publisher who demands the text of the picture book not exceed 500 words won’t even blink when the backmatter adds another 800 – 1000 words to that count. Publishers understand that backmatter helps sales, especially to school and library markets.

The presence of backmatter can also relieve some of the pressure on the writer who desperately wants to share all the cool things they discovered while researching the story. As a result, writers should keep track of everything during the research process, because much of that could fit into a great, beefy collection of backmatter.

For example, suppose you are writing a historical picture book story about a little girl who worked in a mill long before laws about child labor were passed. Obviously, a story like that will benefit from backmatter about child labor, so in your query, you might say, “Planned backmatter for this book includes historical photos and an author’s note about my discovery that my great-grandmother worked in a mill when she was a child.”

Keep in mind that your publisher may have ideas about your backmatter as well and that your plan may change during the publishing process. So, gather materials to include in backmatter, but be open to the different directions your backmatter may take when working with your publisher.

“In my opinion, it’s the books where you don’t expect it—books like going-to-bed books—that are the most amazing when you turn the last page and find backmatter.” Heidi E. Y. Stemple

Backmatter can sometimes appear in unexpected places. For example, stories that originate from traditional folktales or fairytales may include backmatter about the original story. In Imani’s Moon by JaNay Brown-Wood (Illustrated by Hazel Mitchell) an author’s note at the end explains the origin of the story and some details of the history of the Maasai people. In Steve Light’s A Spider Named Itsy, a very short bit of backmatter simply presents the children’s rhyme that inspired the story.

One last thing to mention is that this kind of extra information is not limited to books. Nonfiction children’s magazines and literary children’s magazines also add author notes and other such information, either to the beginning or end of a story or as additional information on the magazine’s website. So, even if you’re still focused on magazine writing, backmatter is something to think about.

Now that you know that publishers love backmatter and that it helps with sales to school and library markets, think about what kinds of backmatter you might add to your work in progress to make it even more engaging.

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

Writers can be thin-skinned when it comes to getting feedback on their work. Let’s look at 4 ways to positively deal with constructive criticism!

Rejection is part of the territory when it comes to being a writer. Today we offer reflection for writers to help redirect your efforts after a rejection.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.