1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

As I said last week, every written piece has voice of some sort. It may be a bit lost in the beginning efforts of learning how to write clearly, but it’s there. Voice also changes some over time. That’s because there’s an element of voice that is linked to the emotions and life experience of the writer. How you feel, both about specific things and in general, affects your writing.

Now, let’s take that idea of voice being linked to emotions and life experience and think about it in terms of those books where you don’t want to write in your own voice. Instead, you want to write in the voice of your character.

First person novels are common in young adult and not rare in middle grade. You can even find first person in picture books. A first person book won’t sound like your normal authorial voice because the speaker isn’t you (unless you’re doing something autobiographical). As a result, it’s worthwhile to realize that writers don’t only need to find their own voice, they need to find the voice of a myriad of characters.

Many beginning writers fall into the trap of making every character sound alike because the writer is only just finding his or her voice, and the idea of finding voices for all these other imaginary pieces feels overwhelming. But actually, developing a voice for your characters can be fun and can make everything about writing that character easier and more exciting.

When developing a character voice, there are endless mechanical options. A character might think and speak in very staccato language, using frequent exclamations, short sentences and few modifiers. Maybe one character uses lots of pop culture references and another character is always pontificating on something, tossing in mostly made-up statistics. Maybe still another character has a catch phrase and a different character is constantly saying “um.”

Character voice grows from the character’s emotions, experiences, and personality. A character who has always known a warm-supportive home that encourages and supports trying new things would believably be quite bold. And that boldness would project itself confidently in the character’s voice. The character would likely be less hesitant and would believably make very active verb choices. The character’s inner voice (thoughts) would also be more confident.

Now that wouldn’t mean the character had to be confident or sure all the time. In the face of a very new situation, the character might doubt himself. But in the case of something he has faced before and has the tools to deal with, if you suddenly make the character very unsure and afraid, you’re going to get that “uneven characterization” feedback. This happens when the character behaves (or even speaks) in a way that is inconsistent with the character’s life experience, personality, and emotions. If you want a confident character to doubt himself when facing fairly familiar challenges, you’ll have had to deal him some rough blows in the story plot to undermine that natural confidence.

Equally, if you’ve created a character who has been consistently overshadowed by the bold members of her family and who doubts herself because she’s always been doubted, then her voice will either be very timid (might be a good time to break out that voice that uses a lot of “um” self-interruptions) or will be falsely confident (in a fake it ’til you feel it kind of way). False confidence is very different from real confidence. Real confidence is open to hearing from others and willing to reshape an idea on the spot when getting good input. False confidence is afraid of input and tries to push ahead without listening. Also, the inner voice of a character in the throes of false confidence will be very different (by turns angry and scared) from the projected voice.

One way to become better at character voice is practice. Try writing a backstory for a character you create right on the spot. I’ve done this by picking a photo of a kid (or a drawing of a kid) from an image search. Then I simply begin coming up with personality traits, emotional traits, and background for the character. I allow how the character looks in the picture to help inform my choices.

I also need to decide how much this passion consumes him. Does he see everything around him through a soccer lens? Does he evaluate everyone based on whether they’d make a good forward on a soccer team? Does he ask himself what his soccer hero would do whenever he hits a rough spot? Does he struggle with school subjects that have no soccer significance? How much does his family support his passion? Does his father wish he played a different sport or does he wish he’d take his school work more seriously or is he the kind who coaches from the sidelines? Does his mom weary of the soccer talk or get frustrated with the kid’s lack of enthusiasm for other areas of his life? Does he eclipse siblings or does he lay in someone’s shadow in the family hierarchy? What in his life is behind his drive in soccer?

The more questions I answer, the more the kid I’ve begun making will become someone I know. Now, he’s not me. He wants different things, has different life experiences and different priorities. He isn’t going to have access to my vocabulary, but he will bring in word choices I wouldn’t. To write this kid, I’m going to have to know a lot more about soccer than I do, so I can casually (and correctly) put soccer terms and sports star references into this kid’s mouth. I’m going to need to get to know him and it’s going to take some work on my part.

Every kid character who has ever become a cultural phenomenon was very real for the creator first. A character you don’t invest in will be a character the reader cannot invest in either. So dig, research when you have to, and don’t shy away from the work when the character seems to be driving you to it. The more you trim back on a character solely so you won’t have to do the work to make him real, the more you short change the reader, the story, and yourself as a writer. And the more you weaken your ability to give him a true voice of his own.

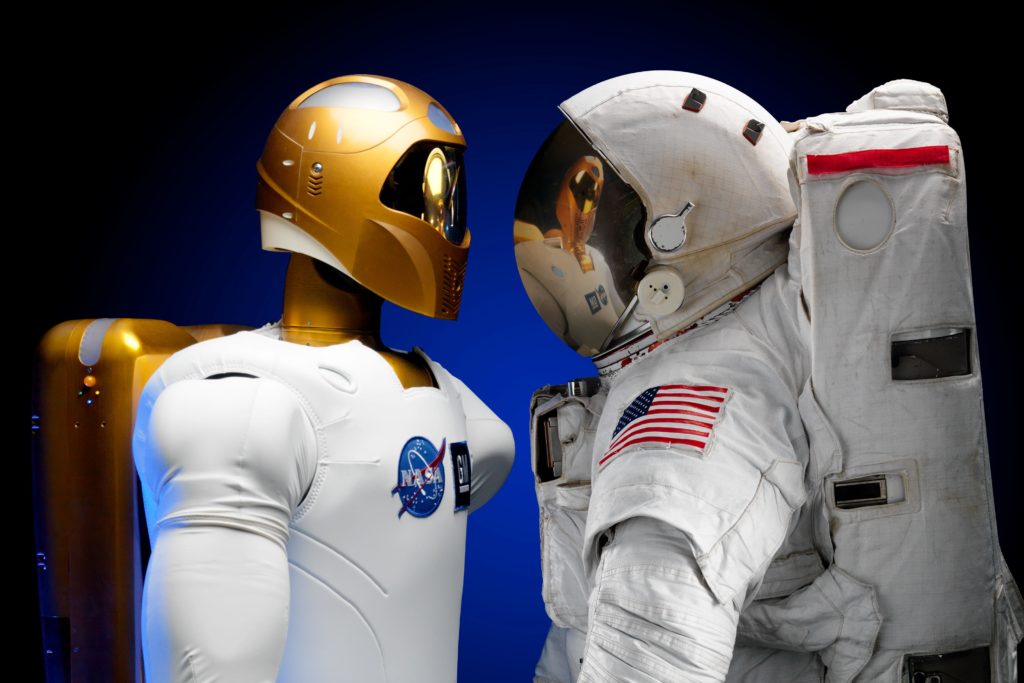

As I delve deeper into character creation, story plots tend to simply pop up. A long time ago, I thought about a character who lived on a relatively new space colony (about a dozen years old or so). The environment was potentially dull as it would logically involve a lot of rules and a lot of limitations. For the adults, this is a new and fascinating world filled with things to discover. For the kids, it’s probably a place with a lot of rules and very little hands-on discovery at all. We tend to try to keep our kids away from the really dangerous stuff where the excitement is.

Many writers begin stories with character creation. They write the story that this character belongs in. And many times they tell the story in the voice of the character because the depth of character creation has enabled them to hear this imaginary person. When writers speak of their characters talking to them, they mean they’ve found the voice of this character clearly because they’ve made the character real in their own heads. This is one reason why trying your own character creation exercises can sometimes pay big rewards. It has for me. Maybe give it a chance to work for you.

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

7 Comments